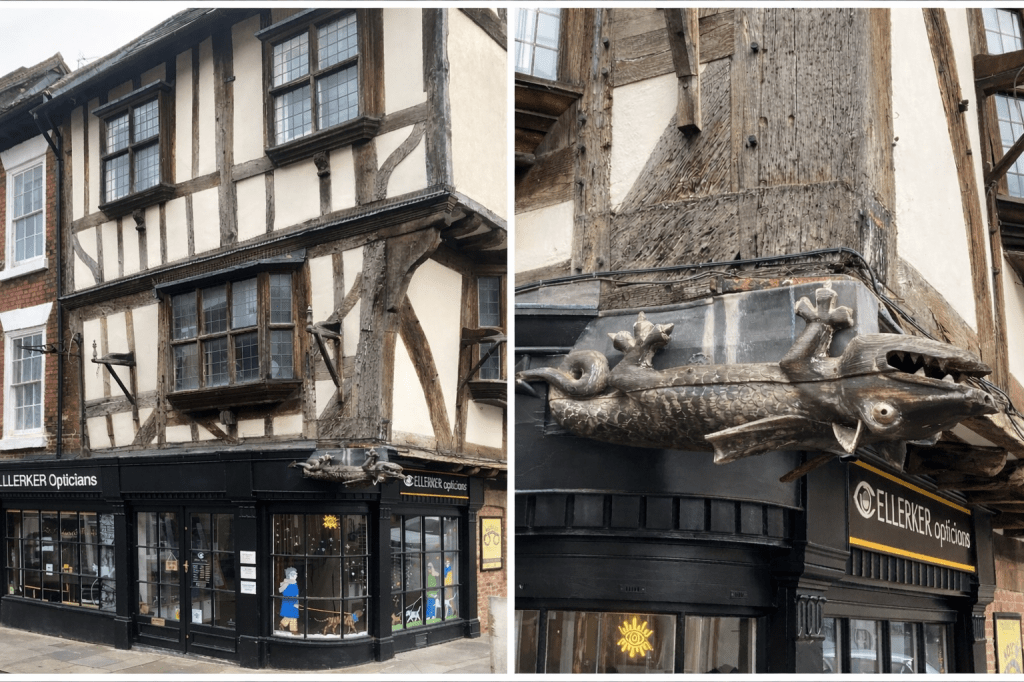

Shrewsbury has plenty of Tudor buildings. But only one features an upside-down carved dragon.

On reflection it’s clearly not 15th century, unlike the building itself. A little research revealed that Puff the dragon – as locals call him – was carved in the 1980s and installed to cover an exposed beam.

Puff might not be original but he feels entirely at home. He solved a problem and speaks the same architectural language as the rest of the building.

Now consider a pair of proud stone lions flanking the driveway of a brand-new house. Something grates. Perhaps because the lions imply a lineage the house hasn’t had the chance to earn.

The lions aren’t the problem. It’s the context. At the end of a gravel drive, in front of a house that has gathered its own history, they make sense. On a new-build with block paving, they feel premature.

Puff, on the other hand, fits.